Dual pricing (Thai price and farang price) has long been a subject of contention among the expat community.

While most holiday makers probably don't realise a dual economy exists, even though they may pay up to a third more than a Thai would on many items in tourist area, the large majority of expats grumble at paying more for goods and services than locals.

And this is totally understandable. I mean, once you’ve lived in a country for five or so years, you’d expect to be treated like a local, right?

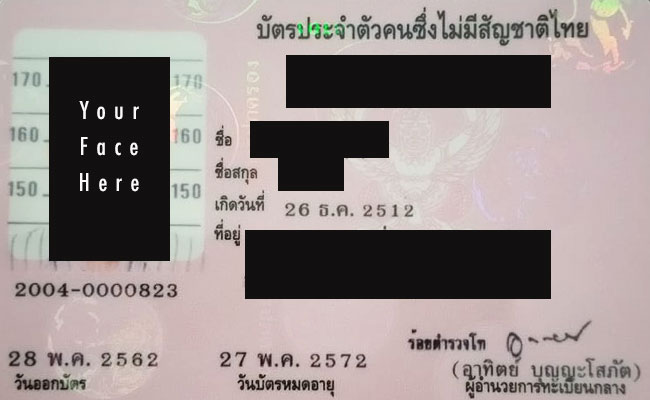

Multiple (dual) pricing evolved from the barter economy. (Image Credit: Samuel John Roberts @ Flikr)

It isn’t just street stalls and local shops that operate a dual economy, either. Many museums and national heritage sites stipulate dual pricing on entry, which is never usually more than a hundred Baht’s difference, but enough of a difference to make one feel discriminated against.

However, the reality is that outside of the tourist hotspots, purchases from local markets are generally priced the same, unless you know the owner personally. But when it comes to museums, heritage sites and other attractions, foreigners are usually expected to pay more.

But before we spout off about Thais being racist and how unfair it is, it is important to understand why a dual economy exists, and how it is potentially beneficial to some Thais — even though we might lose out at times.

A Sprinkle of Historical Context

The first mistake Western critics tend to make is to compare the evolution of Thailand's economy side-by-side with that of the UK or US, for example.

Thailand's capitalist economy as it exists today is very immature, and is often referred to as a pseudo-capitalist economy that presents itself as such but operates quite differently in many pockets of the country.

In fact, many of the older generation still alive today will have grown up in a rural barter-type economy. Indeed, my wife's grandmother did.

She still talks of swapping goods in her childhood and people lending their skills to each other in exchange for food and household essentials.

Only one hundred odd years ago the majority of the male population in Siam (Thailand) was in the service of court officials, while their wives and daughters may have traded on a small scale in local markets. And only at the end of World War 2 did Thailand's economy truly begin to become globalised.

Also consider that Thailand has not experienced the immigration and subsequent “multi-culturalism” that Europe and the US has. In comparison, Thailand has very few foreigners, and trade laws and the buying of land and housing is still very restrictive for foreign nationals.

Thais still very much do things the “Thai way”, and in the way they see fit.

And yes, for many this means ‘preference pricing', which, by the way, is not restricted to foreigners. I for one get my fruit cheaper than other local Thais because I am friends with the seller. This is a friendship built over around five years. That's how things still work here. Communities are very much localised, even in a big city like Bangkok.

Money Vs. Feelings

The fact that the difference between the “Thai price” and the “farang price” is usually quite small — certainly for entry to heritage sites and museums — suggests the grumbling is more about feelings that money.

This is understandable. It is a feeling of being discriminated against, a feeling that no matter how long we’ve been in the country we will always be treated as, and identified as, foreigners (“farang”).

On the face of it, this differential treatment is prejudice, and I’ve even heard some liken it to 50s America and the preferential treatment of whites over blacks. But the reality is it’s nothing like that at all.

The dual economy is born out of simple economics. Nothing more. If you believe that the elimination of dual pricing would promote integration, and give expats more “status” as citizens of the country, you’re living in a alt-left dreamworld.

This might sound harsh, but if you think you’ll ever be anything more than a “farang” to most Thai people then you should go home now to avoid further disappointment.

In the same way immigrants are just immigrants to most in your home country, to the average earning Thai, you are just another farang with a fat wallet that allows him/her to live a privileged lifestyle in a poor country.

Thailand is a great place to live, but you and I know we’re never going to be considered citizens of the country in any way, even if we went through the hideously long process of obtaining residency.

Thailand is historically very insular. This has promoted a unity of deep national pride, patriotism and self-identification with flag and country. Anyone outside of that will always be “a farang”.

I point to the words of the Thai national anthem: The land of Thailand belongs to all the Thais, Their sovereignty has always long endured.

No matter how well I understand Thai, no matter how long I’ve had a Thai partner, no matter that my child is half-Thai and no matter how many Thai friends I have, I am, and always will be, a farang. And this is a classification I accept as part of being a foreigner living in a foreign country.

I can’t roll up to Doi Suthep temple in Chiang Mai and say, “Can I pay the Thai price to get in because my wife is Thai?” Or, “Can I pay the Thai price because I’ve poured countless pounds into the Thai economy over the last seven years”. No, because I am not Thai.

✓ Your Next Read: 12 Best Bangkok Markets

An Ethical But Contentious Reason for the “Thai Price”

The reality is that dual pricing has evolved with Thailand; its existence is a natural one that evolved from the market/bartering culture — as it has done in numerous Asian and Middle-Eastern countries. Friends, family and regulars tend to pay less. It's quite simple.

The same is true in some countries of Europe. Ever been to Italy? Go to the market with a local and I guarantee you will get that handbag much, much cheaper! See Greece for reference too.

Where entry to attractions and heritage sites is concerned, it has to be considered that the pricing is based on economics and not prejudice. The average wage is less than 10,000 Baht a month, and most Thais are earning little more than 300-400 Baht a day.

So, let's say I want to take my wife and daughter to a museum on the weekend, and an average earning Thai guy wants to take his family too. If I earn 150,000 Baht a month, and he earns 15,000 Baht, and the entry fee is 300 Baht for adults, he needs to spend more than a day's wages for an outing that every father can easily afford for his family.

In short, I don't mind if his and his wife's entry is subsidised by the government and that they only pay 100 Baht each to get in.

Who would have a problem with that?

Who would have a problem with paying a little more than someone else because they earn 10x more, if it meant their family could enjoy the same social outing?

If I am asked to pay more than the average Thai for entry to certain places because I earn more then I don't mind — if that little bit more is kept at a reasonable ratio.

I am privileged to be able to afford to live here and consistently enjoy myself in nice hotels and swim in the waters of beautiful beaches, and to visit amazing temples and see wonderful landscapes.

The majority of Thais will never be able to take such a holiday in a foreign land. In fact, the majority of Thais have never visited the beautiful islands and wonderful corners of their own country.

So I don’t mind that I pay 100 Baht more for entry to a museum, or 50 Baht more for a t-shirt at the market by the beach.

As a resident (I don’t have official residency) I am privileged to live in a nice apartment, and to be able to afford to eat in lovely restaurants and enjoy all the city has to offer. Again, way above and beyond the means of the average Thai person.

When I say the average Thai, I am referring to the 17 million Thais who earn under ten thousand Baht per month, most of whom, according to a recent bank survey, are in debt to the tune of an average of 150,000 Baht; debt that continues to grow at between 6-20% depending on the mood of the debtor’s loan shark.

Even the lowest paid expat jobs in Thailand massively outweigh the average Thai wage; so should we continue to grumble and begrudge those with very low salaries access to museums and local attractions at a discounted rate?

When we complain how unfair it is that a dual economy exists, we should think for a moment: do we want museums and places of cultural interest to solely be accessible to foreigners and middle/upper class Thais by there being one price for all?

Are we happy to stop the kids of an average earning Thai family going to the places we like to visit just because we feel discriminated against?

Or do we want it the other way around, where everyone pays the “Thai price”. That way, we, along with the Thai middle and upper classes, get to clasp even tighter onto our purse strings, a solution which would no doubt contribute to lowering the wages of those working for state-run museums, national parks and other places of interest.

✓ Your Next Read: Exploring Klong Thom Market

But What About Foreigners Who Earn Low Wages & Rich Thais Who Get Thai Price?

The big problem with the above is that there are lots of well-off Thai people who get the Thai price when they can clearly afford to pay more than the average foreigner.

But then we can’t dismiss 17 million other people on that basis, can we?

So there has to be a better way.

In a country with such huge inequality, there are sectors of society who do need a discounted rate on goods and service.

Most families can't even afford a trip to the cinema, or a take-away pizza. There is no social welfare system to speak of — no food stamps, no child benefit. Though there is a good 30-Baht health scheme.

It is also problematic for those foreign nationals who earn very little too. I was shocked to see that some of the agencies on my job board were offering such low wages to Filipino teachers. They too, like most Thais, would struggle to live on such wages in Thailand.

So that begs the question: Could this whole dual pricing thing be solved with a simple card scheme?

For example: If you earn under x, you get a card that entitles you to y at a discounted rate. y being entry to national parks, museums and other places of entertainment run by private companies that could sign up to the scheme too.

Thoughts Going Forward…

I have never bought into the notion that dual pricing is a prejudicial war on foreigners. It is something that has been evolved and become outdated. In rural communities and market trading circles it has historical roots in the barter economy — as it does in many other countries.

Things have levelled out somewhat over the past few years, though, and vendors often make a point of telling customers (Thais included) that it's “same price” for all.

But where market shopping in tourist areas is concerned, a deal can usually be struck outside of the given price on most things. And would we want that aspect of tiered pricing to disappear? Many tourists enjoy this aspect of holidaying in Thailand.

In the immediate term, if you live in Thailand and want to avoid paying more than the locals, you should definitely learn to speak Thai so that you can engage with sellers in their native language.

By making a little effort to learn the language, you’ll be able to bridge the gap and integrate more with the local community. You’ll be able to strike up a conversation and ask for “Laka con Thai” (Thai price).

Think how you feel about foreigners who don't bother to learn the language in your home country. If you live in Thailand but speak no Thai, how can you expect to be perceived as anything else other than “just another foreigner” enjoying the fruits of the country but with no interest in learning the language?

Back to the main point of disgruntlement though: Prices have been creeping up for foreigners over the past few years, with entry to some historical sites at least 2-3 times the Thai price. This has to stop; simply because it creates ill-feeling, and because not all foreigners earn 2-3 times that of the average earning Thai.

I suggest that the authorities get rid of dual pricing and look at creating a scheme where access to museums, national heritage sites, local attractions and some other goods and services are provided cheaper to those below a certain income threshold.

This will enable poorer families, both Thai and foreign, to have more freedom; to take the kids out to events and activities on the weekend.

It would also enable poorer families to save more money. And who knows, one day they may be able to start a pension, send the kids to university, or at the very least enjoy a holiday to the beach in their own country, or a trip to the cinema once in a while.

Updated: September 2017.

Last Updated on

Teknik Komputer says

Jun 06, 2023 at 5:08 pm

TheThailandLife says

Jun 06, 2023 at 5:31 pm

Ken F says

The bottom line is any country has the right to make up rules for people who are guests in their country. And these rules are usually going to be different than the rules are for its own citizens. It’s no different than if I have guests staying in my house for a few days. Just because those guests are not allowed to do everything in my house that my family and I can do does not mean I am racist towards them or that I am discriminating against them. My house, my rules! Of course, I’m not going to charge my guests money to use the toilet but even if I did, no sane, rational person could see this as being “racist” or even “discriminatory” so long as I am treating all my guests the same.

By the way, someone below mentioned dual pricing on condos but this is not actually a case of dual pricing, per say. After all, all real estate prices are driven solely by supply and demand no matter what country you are in. And since less than 50% of the units in a given condo can be sold to foreigners in Thailand this creates what is basically two completely different and separate real estate markets within an area and even within and individual condo complex itself. And luckily for Thais this means that the huge numbers of foreigners buying condos in Thailand drives up mostly the prices on other units available for foreign purchase and not so much the real estate market in general. I’m sure many Americans wish we had the same policy there where people in some cities can no longer afford to buy houses in their area after an influx of wealthy Chinese investors has driven home prices sky high. If only a minority percentage of those houses were available for foreign purchase however then maybe some of those locals would still be able to afford a house in their own city. Anyway, since foreigners will pay more for property in Thailand this drives up the asking prices for those units in Thailand that are available to foreign buyers, so you will likely be unable to negotiate as low a price as you would be able to on a Thai market condo. Of course, if you are buying a used condo which is already owned by a foreigner you can still find some great deals sometimes depending on how motivated the seller is. In any case, this is no different from property owners in the USA asking for more for a house that is in a very desirable area in which more people with high salaries will be competing to buy the house. Simply put, there is more competition in the foreign available condo market which means more people with more money to throw around wanting to buy, and this and this alone drives up the prices. And if the Thai government changes its policy then foreign investors would be driving up real estate prices for everyone in the popular areas of Thailand and not just for other foreigners.

Anyway, I can certainly understand people being unhappy about dual pricing, particularly if they are taxpayers. After all it was this kind of anger over the whole “taxation without representation” thing that caused those North American colonists to revolt against British rule in the first place and which led to the formation of the United States of American. Still, when people get this butt hurt over something as trivial as this very limited dual pricing scheme I have to think it's due to the fact that some Westerners just have a grandiose sense of entitlement these days. Anytime they encounter a country in which they don’t have all the exact same rights and privileges that they would be afforded back in their own country they cry foul. These people remind me a bit of small children, always whining about this or that “not being fair” - to which my parents would often respond “who said the world was supposed to be fair”. This attitude has gotten so bad in the USA in fact that we frequently advocate for issues – and win - under the guise that they are equal rights issues when in fact they often are not. For example, nudists are not being deprived of their civil rights simply because they are not allowed to be nude in public places everywhere. And yet the way things are going they might just win the argument that they are being deprived of equal rights one of these days. And if this does happen it will probably happen in San Francisco first. Even as a very liberal minded person myself I think this whole fairness for all thing has gotten a bit out of hand and is ironically only serving to create a more oppressive society overall. Society at large should not have to bend over backwards to appease every single overly sensitive individual or small group on the planet. You cannot please everyone or make everyone 100% equal and when you try to do so you just end up creating a living hell for all.

Back to dual pricing though, why would it upset me when it has only affected me 3 or 4 times in the past 30 years. If I were going to get upset over price gouging it would probably be over something that effects me on a daily basis. For example, Phuket is so ridiculously overrun with tourist right now (mostly Russians, Eastern Europeans, and Western Europeans) that some places have started jacking up prices in ways I have never noticed in the past. For example, about 4 weeks ago they raised the entrance fee to paradise beach from 100 baht per person to 200 baht per person. This includes the beach chair rental of course but it’s so crowded now that a chair will likely not even be available. And at Kata Beach even if you can manage to find an open beach chair you can no longer rent a single chair but rather you must rent them in pairs (maybe they did this in the past and I just forgot). This means that if you go alone you will still be paying 200 baht. Still, it is what it is, and this is how the concept of supply and demand works everywhere in the world.

Jan 10, 2023 at 5:39 pm

sam hayman says

Dec 29, 2022 at 6:30 pm

TheThailandLife says

Dec 29, 2022 at 7:53 pm

Evan says

Jul 13, 2022 at 5:32 pm

TheThailandLife says

Jul 13, 2022 at 5:32 pm