Thailand's northern regions are home to fascinating communities of hill tribes, each with unique customs, dress, and ways of life. These communities, predominantly located in the mountainous regions near Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, and Mae Hong Son, are integral to the country's cultural mosaic.

Most of these tribes migrated to Thailand over the past several centuries, driven by a combination of factors including conflict, poverty, and the search for arable land. Originating from regions like Tibet, southern China, and Myanmar, they gradually settled in Thailand's remote highlands, where they could maintain their distinct identities while adapting to local environments.

However, despite their long-standing presence, many hill tribe members face challenges related to unsettled legal status and limited citizenship rights. Some tribespeople lack Thai citizenship, which restricts access to education, healthcare, and legal employment opportunities. This has left certain communities vulnerable to exploitation and poverty. Efforts have been made by the Thai government and NGOs to address these issues, but the process of granting citizenship remains complex and bureaucratic, often leaving many hill tribe members in limbo.

Here’s an overview of the most prominent hill tribes of Thailand.

Contents

Hill Tribes of Thailand

Lawa

A Lawa woman using traditional weaving techniques. Image courtesy of Green Trails.

The Lawa are one of the oldest indigenous groups in Thailand, believed to have lived in the region long before the arrival of the Tai people who now make up the majority population. They are often regarded as part of Thailand's pre-Thai population, with their history in the region stretching back thousands of years.

The Lawa are an Austroasiatic people, closely related to the Mon and Wa ethnic groups. Their language, also called Lawa, belongs to the Mon-Khmer branch of the Austroasiatic language family. Despite the rich linguistic history, the Lawa language is considered endangered, with younger generations often adopting Thai as their primary language due to integration with mainstream society.

The Lawa are primarily subsistence farmers, cultivating rice, maize, and vegetables in the highlands. Their farming methods traditionally include swidden, or slash-and-burn agriculture, though modern practices are increasingly adopted. They also engage in animal husbandry and produce handicrafts, such as woven textiles and baskets.

Their social structure is traditionally based on village communities led by elders who make decisions and mediate conflicts. Spiritual beliefs are deeply rooted in animism, with reverence for natural spirits and ancestors. Rituals and ceremonies often involve offerings to ensure harmony with the environment and to protect against misfortune.

Traditional Lawa clothing reflects their cultural identity. Women often wear black or dark-colored garments adorned with colorful embroidery, while men typically wear simple, practical attire suited to farming life. Ceremonial clothing is reserved for special occasions and festivals, which often feature dance and music unique to the Lawa culture.

Efforts are underway by cultural organizations and researchers to document and preserve Lawa traditions, language, and history, ensuring that their rich heritage continues to thrive.

Lisu

Lisu women in traditional dress. Image courtesy of My Chiang Mai Tour.

The Lisu people originate from Tibet and southwestern China, migrating to northern Thailand in the 19th century due to conflicts, population pressures, and the search for fertile land. Today, they make up approximately 4.5% of the hill tribe population in Thailand.

Divided into two main subgroups, the Flowery Lisu and the Black Lisu, this community retains a strong cultural identity. Their language, part of the Tibeto-Burman family, plays a vital role in preserving their heritage. Traditional governance is often managed by elders, who mediate disputes and oversee rituals.

The Lisu belief system is a blend of animism, Buddhism, and, more recently, Christianity. Spiritual practices are central to their culture, with rituals aimed at maintaining harmony with the natural and spiritual world.

Lisu women are renowned for their colorful, geometric-patterned dresses, complemented by silver jewelry, while men typically wear loose pants and long-sleeve shirts. Their artistry extends beyond clothing to include beadwork and textiles, which are popular among tourists and collectors.

Traditionally reliant on subsistence farming, the Lisu cultivate crops such as rice, corn, and vegetables. In recent years, they have transitioned to cash crops like coffee and tea, reflecting their adaptability to modern economic demands. However, traditional slash-and-burn farming methods, once vital for survival, have raised environmental concerns, leading to efforts to adopt more sustainable practices.

The Lisu New Year is a vibrant celebration featuring music, dancing, and communal feasts. Despite modern influences, these traditions and festivals remain a cornerstone of their identity.

Mien (Yao)

A Mien woman in traditional clothing. Image courtesy of Union of Hill Tribe Villages.

The Mien, also known as the Yao, migrated to Thailand from southern China and Laos, primarily due to political upheaval and conflict, including the Vietnam War. Today, they reside in Thailand's northern highlands, where they maintain their rich cultural heritage.

The Mien people speak the Iu Mien language, part of the Hmong-Mien (Miao-Yao) language family. As a tonal language, the meaning of words changes with pitch, adding complexity and musicality to their speech. Historically, the Mien had no native writing system, relying instead on Chinese characters for some written communication. Modern efforts have introduced Romanized alphabets to preserve their language.

Mien women are renowned for their intricate embroidered tunics and turbans, often adorned with bright red and gold threads. Their traditional attire reflects their artistic craftsmanship, which also extends to the production of silver jewelry and vibrant textiles.

Agriculture remains a cornerstone of Mien livelihoods, with rice farming being their primary activity. They also cultivate other crops and produce handicrafts, contributing to both subsistence and trade. The Mien exhibit strong Confucian influences, particularly in their family-oriented rituals, such as weddings and funerals, which often incorporate elements of Taoism, Buddhism, and animism.

Festivals, like their unique observance of Chinese New Year, showcase their rich cultural tapestry, blending Chinese and indigenous traditions.

Palaung

Palong women in Mae Chon village. Image courtesy of Green Trails.

The Palaung, or Dara’ang, are a smaller minority among Thailand's hill tribes, with their origins tracing back to the Shan State of Myanmar. Over the years, many Palaung migrated to Thailand to escape conflict and political instability in Myanmar.

There are three main sub-groups of the Palaung: Pale, Shwe and Rumai.

The Palaung people belong to the Austroasiatic language family, specifically the Mon-Khmer group. This linguistic connection ties them to ancient civilizations in Southeast Asia. They speak Palaungic languages, but due to their interactions with neighboring groups, many also speak Shan or Thai for practical communication.

Palaung women often wear brightly colored sarongs adorned with horizontal stripes, along with blouses that feature unique embroidery. A striking feature of Palaung attire is the use of silver belts or hoops worn around the waist. Men typically dress in simpler garments but retain elements of their tribal heritage in the form of woven fabrics.

Agriculture is the backbone of Palaung livelihoods. They primarily cultivate tea, which is a significant economic and cultural element for the community. Many Palaung villages are surrounded by lush tea plantations, where families have been involved in the meticulous art of tea production for generations. They also grow rice, vegetables, and fruits in terraced fields. In addition, the Palaung practice traditional weaving, producing textiles that reflect their cultural heritage.

The Palaung traditionally follow Theravada Buddhism, but their beliefs are often intertwined with animism, reflecting a deep connection with nature and the spiritual world. They revere spirits of the land, forests, and ancestors, and many of their rituals aim to maintain harmony between these forces and their community. Shrines and altars can be found in their villages, often used for offerings and ceremonies during festivals.

Karen (Kariang)

A Karen hill tribe family. Image courtesy of Chai Lai Orchid.

The Karen, or Kariang, are one of the largest and most well-known hill tribes in Thailand, with a population of over 1 million. Originating from Myanmar, they began migrating into Thailand centuries ago, primarily due to conflicts and economic opportunities. Today, they are predominantly found in the northern and western regions of Thailand, especially near the borders of Myanmar.

The Karen are divided into several subgroups, with the Sgaw Karen and Pwo Karen being the most prominent in Thailand. They speak distinct dialects within the Tibeto-Burman language family, and their languages have no traditional writing system. However, Romanized alphabets and Burmese scripts have been adopted in modern times for written communication.

The Karen are deeply spiritual, with animism and ancestor worship forming the foundation of their traditional beliefs. Some groups have adopted Christianity or Buddhism, often blending these religions with their animistic practices. Rituals to honor spirits, protect homes, and ensure agricultural success are integral to their way of life.

Karen women are known for their handwoven tunics and dresses, often adorned with intricate patterns and vibrant colors. Unmarried women traditionally wear long white tunics as a sign of purity, while married women opt for colorful designs. Men wear simple loose shirts and pants, often in earthy tones, reflecting their connection to nature.

The Karen have a long history of sustainable farming practices, with rice as their staple crop. Indeed, one of the most notable Karen traditions is the “Khao Ho” or “Eating the New Rice” festival, which celebrates the rice harvest and gives thanks to spirits for a bountiful crop.

Karen villages are tightly knit, with decisions often made collectively under the guidance of elders. Their houses are typically built on stilts, with bamboo and thatch as the primary construction materials, blending seamlessly into the forested landscapes they inhabit.

Padaung (Kayan) – Long Neck

Paduang women wearing the traditional neck coils. Image courtesy of Think Global Heritage.

The Paduang, also known as Kayan or Kayah, or Long Neck people, belong to a subgroup of the Karen hill tribe. They are originally from Myanmar's Kayah State but have migrated to Thailand, primarily to escape conflict in their homeland. Today, many reside in villages in northern Thailand, particularly in areas around Chiang Mai, Mae Hong Son, and Chiang Rai, often as refugees without full citizenship rights.

The distinctive feature of the Padaung women is their practice of wearing brass coils around their necks, giving them the “long neck” appearance. This tradition begins when girls are young and continues as more coils are added over time, pushing down the collarbone and compressing the ribcage to create the elongated neck effect.

Research has shown that the wearing of coils weakens neck muscles and damages the jaw, collarbone, and ribs. The practice is tied to cultural identity, myths of beauty, and social status, although its origins remain debated among historians.

In recent years, the Long Neck Karen villages have become a significant tourist attraction in Thailand, sparking debates about cultural preservation versus exploitation. Some women wear the coils as a way to sustain their livelihoods through tourism, while others forgo the practice, embracing modern lifestyles.

Hmong

Hmong kids posing for a picture in traditional attire. Image courtesy of Chiang Mai Tour.

The Hmong are originally from the mountainous regions of China, Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand. They began migrating to Thailand in the late 19th and early 20th centuries due to wars and political unrest in their home countries. Hmong villages are typically self-sufficient, with homes built using bamboo and wood, and are often located in remote mountain areas.

The Hmong people are divided into several subgroups, the largest being the White Hmong and the Green Hmong. They speak the Hmong language, which is a member of the Hmong-Mien language family. Hmong is a tonal language, meaning the tone or pitch used when pronouncing a word can change its meaning. There is no native writing system for the Hmong language, but the Romanized Popular Alphabet (RPA) is used for written communication in modern times.

The Hmong people are primarily animists, believing in a spiritual world where ancestors and nature spirits play an important role in daily life. They practice various rituals, such as spirit calling ceremonies, to maintain harmony between the human and spiritual worlds. In addition to animism, many Hmong have converted to Christianity or Buddhism over the years, often blending these religions with their traditional beliefs.

Hmong women are well-known for their vibrant, intricately embroidered clothing, which reflects the skill and artistry of their community. The clothing is made from handwoven fabrics, and each garment is adorned with elaborate patterns, often symbolizing family lineage, regional identity, and personal accomplishments. Women typically wear jackets, skirts, and aprons decorated with bright colors, intricate needlework, and silver ornaments. Hmong men wear simple, functional clothing, often consisting of a jacket and pants with a colorful embroidered belt.

The Hmong are traditionally farmers, with rice being the staple crop grown in their highland fields. They also cultivate vegetables, fruits, and herbs, utilizing swidden (slash-and-burn) farming techniques in the forested areas where they live. Hmong women are also skilled in the production of textiles, weaving intricate patterns used in their traditional attire, which is often sold to support their families.

Hmong society is structured around clan systems, with each clan providing a strong sense of identity and social support. The Hmong community places great importance on family ties, and decisions are often made collectively.

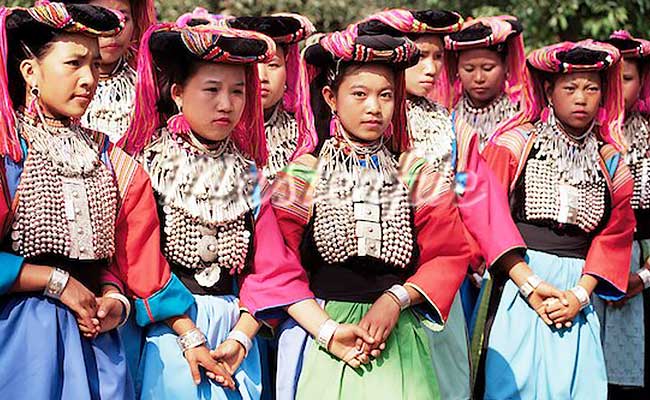

Akha

Akha women celebrating in traditional clothing. Image Courtesy of Chiang Mai Trekking.

The Akha are an indigenous ethnic group who originally hail from the highlands of southern China, northern Laos, Myanmar (Burma), and northern Thailand. They migrated to Thailand in the early 20th century, with many settling in the mountainous regions of Chiang Rai, Chiang Mai, and Mae Hong Son in the northern part of the country.

Today, the Akha make up a significant portion of Thailand’s hill tribe population and are known for their distinctive cultural practices, vibrant clothing, and strong community ties.

The Akha people speak the Akha language, which belongs to the Sino-Tibetan language family. Like many of the other Hill Tribe languages, Akha has no native written script, so modern Akha people use the Roman alphabet or adapted scripts from neighboring languages for written communication.

The Akha are divided into several subgroups based on geographical location and dialect differences, such as the “Upper Akha” and “Lower Akha.” Despite these distinctions, all Akha share common cultural traditions and practices, which unite them as a cohesive group.

Akha women wear brightly colored tunics with elaborate designs, often featuring intricate geometric patterns and vibrant beads and metalwork. One of the most iconic features of Akha women’s attire is their headdresses, which are made from silver coins, beads, and colorful threads, and are often quite large and ornate.

The Akha men wear more simple clothing, typically consisting of a jacket and pants made from dark cloth, with less elaborate decoration than the women’s attire. However, both men and women wear silver jewelry, which signifies wealth and status in the community.

The Akha people are predominantly animists, believing that all natural elements — from the mountains and forests to the rivers and animals — possess spiritual significance. They believe in a complex relationship between humans and the spirits, with rituals designed to maintain harmony and balance. Ancestor worship is central to Akha spiritual life, and each Akha family has a shrine dedicated to their ancestors, where offerings are made.

One of the most significant rituals for the Akha is the New Year ceremony, which marks the beginning of the harvest season. During this event, the Akha people pay homage to their ancestors, make offerings to the spirits, and perform elaborate dances and prayers.

The Akha have a strong sense of identity tied to their customs, and much importance is placed on preserving traditions. Marriage is an important cultural institution in Akha society, and many young people are married through arranged unions.

The Akha people are traditionally agriculturalists, relying heavily on farming for their livelihood, but in recent years, many Akha have shifted to cultivating cash crops like tea, coffee, and strawberries, which are sold at local markets. The Akha people are also known for their handicrafts, including their intricate silver jewelry and textiles, which are sold in local markets and abroad.

Lahu

Lahu women in traditional dress. Image courtesy of Mae Hong Son Holidays

The Lahu people are believed to have arrived in northern Thailand from southwestern China and Myanmar around the 18th and 19th centuries. They are considered one of the more recent groups among the hill tribes of Thailand compared to groups like the Karen or Hmong, who have a longer presence in the region.

The Lahu people likely migrated from the Tibetan Plateau to their current locations in Southeast Asia. Like many other ethnic groups in the region, they are part of the Sino-Tibetan language family. The Lahu language, known as Lahu or Lha, is tonal, meaning that the pitch used in pronunciation can change the meaning of a word; just like the Thai language.

The Lahu are divided into several subgroups based on language differences and social practices. The main subgroups include the Lahu Nyi, Lahu Shi, and Lahu Khao, with the latter being the most widely known.

The Lahu usually live in simple, wood-and-thatch houses. Their villages are typically located in the hills, which allows them to practice agriculture while remaining somewhat isolated from mainstream society. Like most tribes, a Lahu village has its own village headman, who is responsible for making decisions and resolving disputes within the community.

The Lahu also have strong shamanistic practices, with spiritual leaders known as shamans or “Mong” playing key roles in performing rituals and ceremonies to communicate with the spirits and protect the community from harm.

While animism forms the core of their religious beliefs, there has been significant influence from Buddhism, particularly in areas where Lahu communities coexist with Thai Buddhists. In some areas, Lahu people have also embraced Christianity, which was introduced by missionaries in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Lahu are known for their brightly colored and intricately designed clothing. Lahu women wear embroidered tunics, which are often adorned with vibrant geometric patterns in red, blue, and black, with silver decorations. The clothing is complemented by elaborate headdresses made of silver and beads, which are worn during special ceremonies and festivals. The men, on the other hand, wear simpler clothing, often consisting of a tunic and pants.

Silver jewelry plays a significant role in Lahu culture, with both men and women wearing silver necklaces, earrings, and bracelets. The silver is not only a symbol of status and wealth but is also believed to have protective powers against evil spirits.

The Lahu people traditionally rely on subsistence farming, growing crops like rice, maize, and vegetables. In recent decades, the Lahu have expanded their agricultural practices to include cash crops such as corn, coffee, and tea.They have also become involved in handicrafts, producing woven textiles, baskets, and other artisanal goods, which are sold to tourists and collectors.

The Lahu social structure places great importance on family and clan relationships. Marriage is an important rite of passage, and traditional marriages are often arranged by the families. Dowries, typically in the form of livestock or goods, are an essential part of the marriage process.

In Lahu society, elders are highly respected, and their wisdom is passed down through oral traditions. Stories, songs, and customs are taught to younger generations, ensuring that cultural knowledge is preserved and passed on.

Challenges Facing Hill Tribes in Thailand

Economic Marginalization

Many hill tribes live in poverty, relying primarily on subsistence farming to sustain their livelihoods. Access to stable, well-paying jobs is often limited, as geographic isolation and lack of education create barriers to economic advancement. While some tribes have adopted cash crops like coffee or handicrafts to supplement their income, these efforts often fail to provide long-term financial stability. Seasonal work or employment in the informal sector leaves many families struggling to meet their basic needs.

Land Rights Disputes

One of the most pressing issues hill tribes face is the lack of legal land ownership. Many hill tribes reside on land designated as national parks or conservation areas, leading to frequent disputes with local authorities. Without official land deeds, they are vulnerable to eviction and restricted from using the land for farming or development. This not only disrupts their livelihoods but also forces them into cycles of economic instability and displacement.

Cultural Erosion

Modernization and tourism have introduced new opportunities for hill tribes but at the cost of their traditional ways of life. As younger generations gravitate toward urban areas for work or education, the preservation of indigenous languages, customs, and crafts is increasingly at risk. Tourism, while a source of income, often commercializes cultural practices, reducing them to spectacles for visitors rather than living traditions. The result is a gradual dilution of identity and heritage, threatening the survival of their unique cultures.

Addressing these challenges requires thoughtful policies and collaboration between the government, non-governmental organizations, and the tribes themselves to ensure economic inclusion, secure land rights, and the preservation of their cultural heritage.

——

Disclaimer

I have made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information provided in this article about Thailand's Hill Tribes. However, there may be inadvertent errors or inaccuracies. If you come across any discrepancies or outdated information, I encourage you to reach out to me directly.

Additionally, while I have taken care to credit all sources appropriately, if you believe that any image used in this article infringes on your copyright or was used without proper permission, please contact me using the contact form on this site. I will address the issue promptly and remove the image if necessary.

Thank you for your understanding.

Last Updated on

Leave a Reply